Milton’s great theme in Paradise Lost is the fall and redemption of humanity. This too can be seen as “some tragic falling off into difference and desire,” which has been the theme of my last two posts in this series.

Milton treats on a cosmic and theological level what Wordsworth treats on a temporal and personal level, and what Lacan treats linguistically and psychologically, and, in the end, mystically.

Each speaks of the loss of a “perfect” state of being–-a Paradise (the Garden of Eden), or Unconscious Bliss (Child-like Joy & Innocence), or Undivided Wholeness (Pre-Lingual Identity, before I and Other became Two).

And each speaks of an incessant desire to regain what was lost.

For Milton in Paradise Lost the development of humanity is seen as a succession of “falls.” Satan falls from Heaven into Hell. Eve falls into temptation and Adam joins her there. They both fall from grace into disgrace, from innocence into guilt and shame. Then they fall from Paradise, the Garden of Eden, into a life of suffering and toil on earth.

Yet the Fall actually begins before there ever was a Heaven and a Hell, or an Adam and Eve. The Fall is actually a succession of “falls” into ever-increasing difference, loss, and desire. It begins when God, with a Word, divides creation from chaos, splits the Void in two, separates light from darkness, the waters from the earth, the higher from lower, the birds from the beasts, and so on.

We might think of the Big Bang as the first fall or split, when that undivided density of black matter exploded into an expanding universe. Perhaps every act of creation, including the first division of a human egg cell, or when the fist microorganism divided itself from the primordial soup, can be seen as “some tragic falling off” from a first world of undivided wholeness into an ever-increasing world of differentiation and identity.

But all this division is not really the point. It’s an important part of the point–-and essential to it–-but not the point itself.

For Milton, the point is redemption, or paradise regained—reunion with God. After his fall, Adam desires to return to that original state of grace and innocence and unity. The Archangel Michael tells him this is impossible. The knowledge of the Fall—of sin, difference, and death–-will always lie between Adam and his former unknowing bliss.

And yet, paradoxically, Michael tells him, it is Adam’s knowledge of the Fall which will elevate his redemption above the original state. M. H. Abrams in Natural Supernaturalism calls this “The Paradox of the Fortunate Division.”

He writes: “Not only was [Adam’s] fall the essential condition of the Incarnation . . . but also of the eventual recovery by the elect of a paradise which will be a great improvement upon the paradise which Adam lost.”

Michael takes Adam up into a high hill and reveals to him all the good that will come out of evil when redemption takes place: “The earth shall be paradise, far happier place than this Eden, and far happier days.”

Adam replies: “O goodness infinite, goodness immense! That all this good of evil shall produce, and evil turn to good.”

Redemption begins with the first downward step into a differentiation out of which a desire for redemption promises, not reunion, not a return to what was, but something more. Something which far surpasses it.

Through poetry, Wordsworth’s desire to recollect what he had lost as a child, he gains a “sense sublime” that surpasses what had been lost.

Lacan speaks of a similar journey in the development of the psyche. He shows how the quest for reunion with the unconscious bliss we knew as infants is ever present and woven into the fabric of the psychic existence. It is not a conscious choice as with Milton’s Adam, or Wordsworth’s poet. It is experienced as an unquenchable desire for “something more” that haunts all our days.

Lacan locates this “something more,” which is beyond representation, in “feminine jouissance.” He refers to the Bernini statue of St. Teresa, in which he claims, “she is coming, no doubt about it.”

He adds, “Might not this Jouissance which one experiences and knows nothing of, be that which puts one on the path of ex-istence? And why not interpret the face of the Other, as the God Face?”

Lacan tells us: “Psychoanalysis may accompany the patient to that ecstatic limit of the ‘Thou art that,’ in which is revealed the cypher of his mortal destiny, but it is not in our mere power as practitioners to bring him to that point where the real journey begins.”

“Thou art that” is a central motif in Hindu mysticism. It is what the Christian mystic or Zen Buddhist might call the non-ego, becoming conscious of the unconscious, or unconscious of consciousness.

Throughout his 1964 seminars, Lacan alludes to God as “a ground or field,” or some “vast unconscious principle” that lay “outside of the dialectic of scientific certainty and metaphysical doubt”.

But that “face” or “ground” of God which we desire lies beyond language, beyond representation. It is that “ecstatic limit” toward which psychoanalysis can only aspire, but beyond which it cannot trespass. Psychoanalysis, language, poetry, can lead one to the threshold of this “ground,” but it cannot pass through it.

What’s interesting, and comforting, to me, is that we can’t obtain redemption or the poetic mind, let alone “Thou art that,” by going back to what we were in our original state of innocence and bliss.

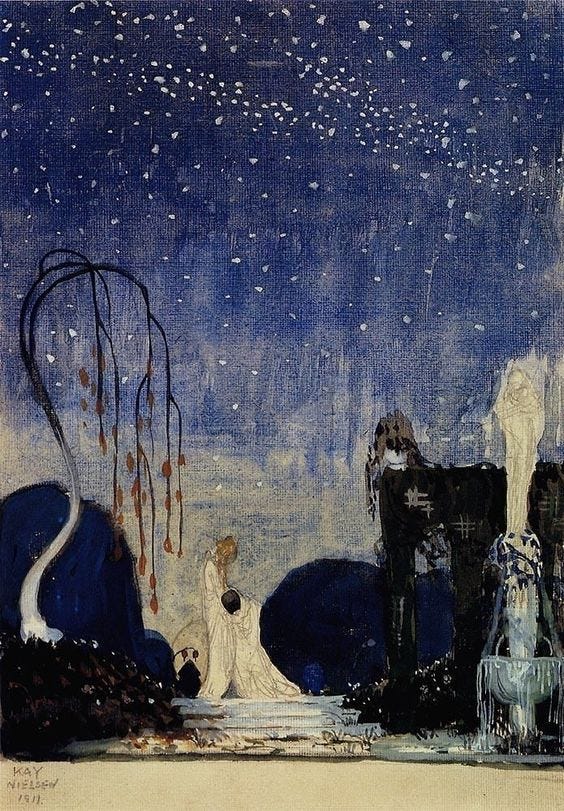

Zen Oxherding picture No. 10 Returning Home

But by moving through our messy lives, experiencing the difference, loss, desire that cannot be avoided, and then reaching beyond that, to “something more,” we may find something that surpasses what we had originally sought.

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

– T.S. Elliot

If you missed the first two parts of this series, you can read them here:

Part One: “Some Tragic Falling Off from a First World of Undivided Light”

Part Two: A Poet’s “Sense Sublime”

If you enjoyed these, you might also want to take a look at Desire for a Higher Kind of Lovemaking.

As always, I’d love to hear what you think about all this, or anything else you’d like to share. As Lacan also wrote, “The purpose of language is not to inform but to evoke responses.”

Lot there, there and enjoyed how you wrapped all this up. I agree with the tat tvam asi of hinduism and reject the escatological fall and return and redemption non-sense. But that makes a good plot and story and so holds dear to our hearts, this story of a kind of revenge and making everything well and good again. Funny while reading this, I kept thinking of Blake - will have to return to his writing (and painting and etching). Essentially Blake sought to slay morality the death child of reason and create liberation through unity with the spirit of all. But essentially, we arrive at a point that we know zip all. We are leaves in a cold stream propelled along, dreaming of the tree.