Language & Literature, Loss & Desire

"Some tragic falling off from a first world of undivided light"

I’ve been thinking a lot about desire and loss lately and how these are the great themes explored over and over again in all great poetry, literature, art, religion, science, psychology, philosophy. Groping for “something more,” something just out of reach. Feeling a sense of loss, of incompleteness, and seeking what will make us whole.

Robert Hass’s poem “Meditation at Lagunitas” speaks to this. It begins:

All the new thinking is about loss.

In this it resembles all the old thinking.

The idea, for example, that each particular erases

the luminous clarity of a general idea. That the clown-

faced woodpecker probing the dead sculpted trunk

of that black birch is, by his presence,

some tragic falling off from a first world

of undivided light.

All the old thinking and new thinking is not only about loss, but also about desire, about returning to that “first world of undivided light.” About regaining what was lost.

“We are all inescapable dualists—for Lacanian, not Cartesian, reasons.” – Charles Alteri

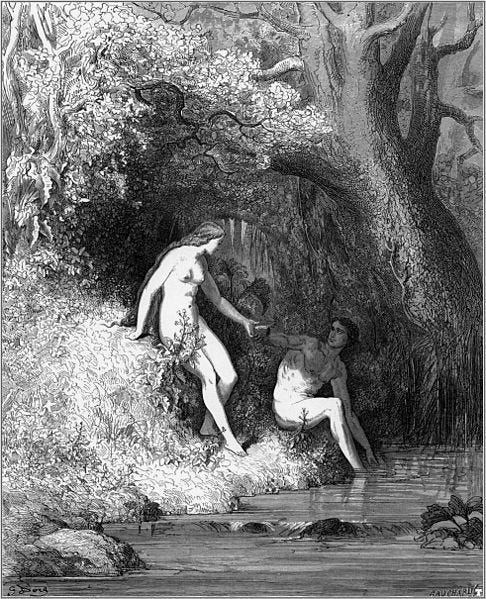

If duality arises from difference, difference from separation, and separation is accompanied by a sense of loss and desire, then it could be said that duality, difference, and desire presuppose “some tragic falling off” from an original–-mythical or otherwise–-world of undivided wholeness.

Milton’s Paradise Lost, Wordsworth’s Prelude, and Jacques Lacan’s lectures on psychoanalysis all repeat at various levels this elemental theme of difference, loss and desire. What Milton treats at a cosmic and theological level, Wordsworth treats at a temporal and personal level, and Lacan treats linguistically and psychologically. In each, however, language is instrumental not only in the initiation of difference, but in the formulation of a desire which may turn it back toward a redemptive reunion.

But the ideas explored are relevant for all of us, for writers in particular, and for anyone grasping at the meaning of life, or seeking a sense of wholeness.

Writers of fiction know that to create a compelling story that keeps readers turning pages we must:

Create a protagonist with an overarching need or desire (derived from some sense of loss, of being wounded, or incomplete)

beset by constant conflict that intensifies and delays achievement of that desire (to gain what was lost, find healing or wholeness)

until that need or desire is eventually realized (or not), but either way,

leaving the protagonist in a better place (happier, wiser, more whole) than where she had been before the story began, having learned something important or significant about herself, the world she lives in, or what it means to be human.

What drives the story and develops the character is a quest to return to wholeness, to regain what was lost. But what is regained is never simply what was lost, but “something more.” Some new realization–-wisdom chiseled from the hard knocks and setbacks of a difficult journey, insights into human nature that will light her path moving forward.

Perhaps we find these stories so compelling because they parallel our own psychic development from the womb to maturity and beyond.

Psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan describes the earliest part of this development as the Mirror Stage. This is where an infant first becomes aware of itself as a self, and where the division between I and Other, subject and object, consciousness and the unconscious takes place.

Lacan explains how an infant cannot differentiate itself from the world around it. Lying on a blanket beneath the trees, it waves its hands and sees no difference between its waving hands and the trees blowing in the wind and its mother’s face as she bends over the child and takes it into her arms. The infant is one with its world, which it experiences as undivided bliss and wholeness.

But this cannot last. As the child grows it becomes more and more aware of difference. It has control over some parts of itself (its hands and feet) while it has limited control over its mother and none whatsoever over the trees. Eventually, the child comes to identify itself with its body and to distinguish itself from other parts of its world, and the individual is born.

Lacan sees this development as a succession of splits or gaps, a sense of separation between I and Other, the knower and what is known. The child experiences this growing awareness and individuation, however, as a sense of anxiety–of separation and loss–and desire, to reclaim what was lost.

This is what the Robert Hass referred to in his poem as “some tragic falling off from a first world of undivided light.” But out of that differentiation between I from Other, painful as it may be, comes a growing awareness of the Other, experienced in all its exquisite particularity.

Out of that “world of undivided light” appears “the clown-faced woodpecker probing the dead sculpted trunk.” Without difference, the split between I and Other, the infinite variety and particular beauties that we now experience with such pleasure would be unknown.

Here’s what’s interesting though: We cannot “know” something without first acknowledging its difference from the knower. Yet, paradoxically, to “know” something, to become aware of its difference, is to “take it in” and make it one’s own–a part of one’s experience or store of knowledge, for instance.

Having suffered the painful split of separation from a world of undivided wholeness, we are now filled with a desire to reunite with what was lost, and the only way we can do this is by “taking in the whole world”—by naming it and knowing it through language, by exploring the world around us, and the world of ideas, and by seeking ever new experiences, insights, and knowledge.

For Lacan, this turning back toward “reunion” is ever present and woven into the fabric of the psychic existence. The gap between I and Other, subject and object, the conscious and unconscious creates, of its own necessity, out of its own “vacuum,” the desire to close the gap.

While this effort to reunite with what was originally lost appears futile in and of itself, it does create some interesting correlations. For “I” defines itself not in itself but through its relationship with Others and the desire to satisfy Others’ desires. There is a kind of overlapping or embrication of identities, which constitutes an intersubjectivity. A sense of “doubleness,” if you will–-standing always within ourselves and outside ourselves at the same time.

This sense of “doubleness” can be seen when we examine our consciousness in relation to the unconscious. What exists prior to individuality or consciousness is the unconscious. The entrance of the subject into a conscious state immediately renders it double. The unconscious both surrounds and grounds the conscious self, but never comes fully within the locus of being—that is, being fully identified.

The content of the unconscious remains, perhaps, a kind of “becoming,” Lacan writes, in that it can potentially become, but once solidified consciously into an identity, ceases to be what it was: unconscious.

Lacan tells us that “the unconscious is structured like a language.” Like language, its function is “not to inform but to evoke responses in the other,” in consciousness. It does this through language, but always inadequately, for language can never fully represent unconscious desire. Always it says both less than what it wants to say and more than what we can understand.

How well this parallels the human dilemma: We are at almost every point less than what we want to be and more than what we can understand. Hence our desire for, our striving toward, that “something more” which we do not fully understand, and cannot articulate. It is something we first glimpsed in our distant past which is no more, and which we seek in a future which has yet to be. We ourselves stand in that gap of now, which is itself a kind of becoming.

Lacan explains the difficulty of our dilemma this way:

“I identify myself in language, but only by losing myself in it like an object. What is realised in my history is not the past definite of what was, since it is no more, or even the present perfect of what has been in what I am, but the future anterior of what I shall have been for what I am in the process of becoming.”

This “process of becoming” is the turf of poets as well as psychoanalysts. And no poet writes more upon this subject or with such longing, perhaps, than William Wordsworth, who wrote in “Tintern Abby”:

Our destiny, our nature, and our home

Is with infinitude, and only there:

With hope it is, hope that can never die,

Effort, and expectation, and desire,

And something evermore about to be.

More from the poets on this topic in my next posts. You can read them here:

I’d love to hear your thoughts on this. Please share below.

“Lacan explains how an infant cannot differentiate itself from the world around it.”

This sounds very much like, or that it has parallels with what psychologist call ‘theory of mind’ and the way children learn to separate themselves from the mother. I have had to read up a lot about it with my son being autistic. For autistics, the realisation the are indeed separate and the implications of this comes later than in most people. My son when he was little was always shouting “Where am I?” He meant “Where are you?” I found it fascinating.