Landfall in Nuka Hiva.

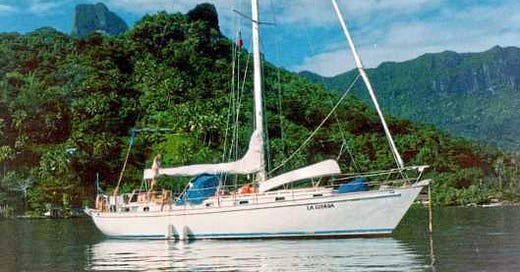

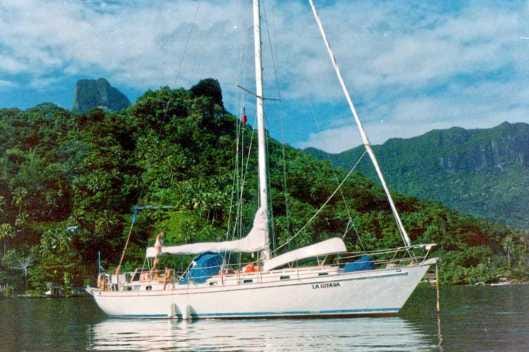

Out of the sea rose a lush-green mountain ribboned with waterfalls. After 29 days at sea aboard La Gitana, it seemed a small miracle to arrive here so precisely with only a sextant and the stars to guide us. Our first tropical landfall on our round-the-world journey.

Walking through the village, down narrow, winding roads, past pastel-colored houses surrounded by gardens overflowing with flowers and dense tropical foliage, melting in the heat and humidity and the perfumed air . . . . I felt physically and mentally assaulted, overcome by the intensity of the colors and the abundance of the beauty that surrounded me, shattering the senses. Sight, smell, and sound washed together, streaming through me, carrying me away.

This sense of being awash in or assaulted by color stayed with me and revisited me often on our travels through the South Pacific. Sometimes it was a soft, sensual immersion. Sometimes a harsh, brutal slaying. It knocked me off my feet and broke me open. I swallowed it whole.

The poem that had been brewing in my mind all this time, that I wrote about in another post, came together one day in Moorea in the Tahitian Islands. La Gitana was anchored at the end of a deep cove with green mountains walls on one side and a valley opening up between them. On the other side was a bluff with a small cottage surrounded by a flower garden that trailed down the rocks toward us.

Each afternoon magnolia tree blossoms would drift down into the sea and our daughter rowed among them, gathering the sweetly scented flowers. As beautiful as it was down here on the water, I kept wondering what it would be like up there, in the garden on the bluff, walking among flowers.

At the time I was reading Creativity and Taoism – A Study of Chinese Philosophy, Art, and Poetry by Chang Chung-yuan. He writes of the “interpenetration of Nature and Man” by which ”the artist reveals the reality concealed in things [and] sets it free.”

One of my favorite drawings in the book is Flower in Vase by Pa-ta san-Jen(1626-1701). There is nothing beautiful or delicate or uplifting about the drawing, but it affected me deeply, physically, like a punch in the gut.

Chung-yuan explains the drawing this way: “No attempt is made at beauty or refinement of form, merely the primary essentials of the object are given. Here we see innocence or the quality of the uncarved block at its best. What is within is manifested without.”

The uncarved block is elsewhere identified as “original simplicity,” “simple, plain,” “obscure and blunt,” “unattached and depending on nothing.” It has “no artificial efforts” or “ intellectual distinction.” It is “not self-assertive but disappears into all other selves” thereby “moving within the forces of the universe.”

Heady stuff. All I know is that the drawing affected me much the same way I felt when being “assaulted by color” on Nuka Hiva. Something in me was shattered and released at the same time.

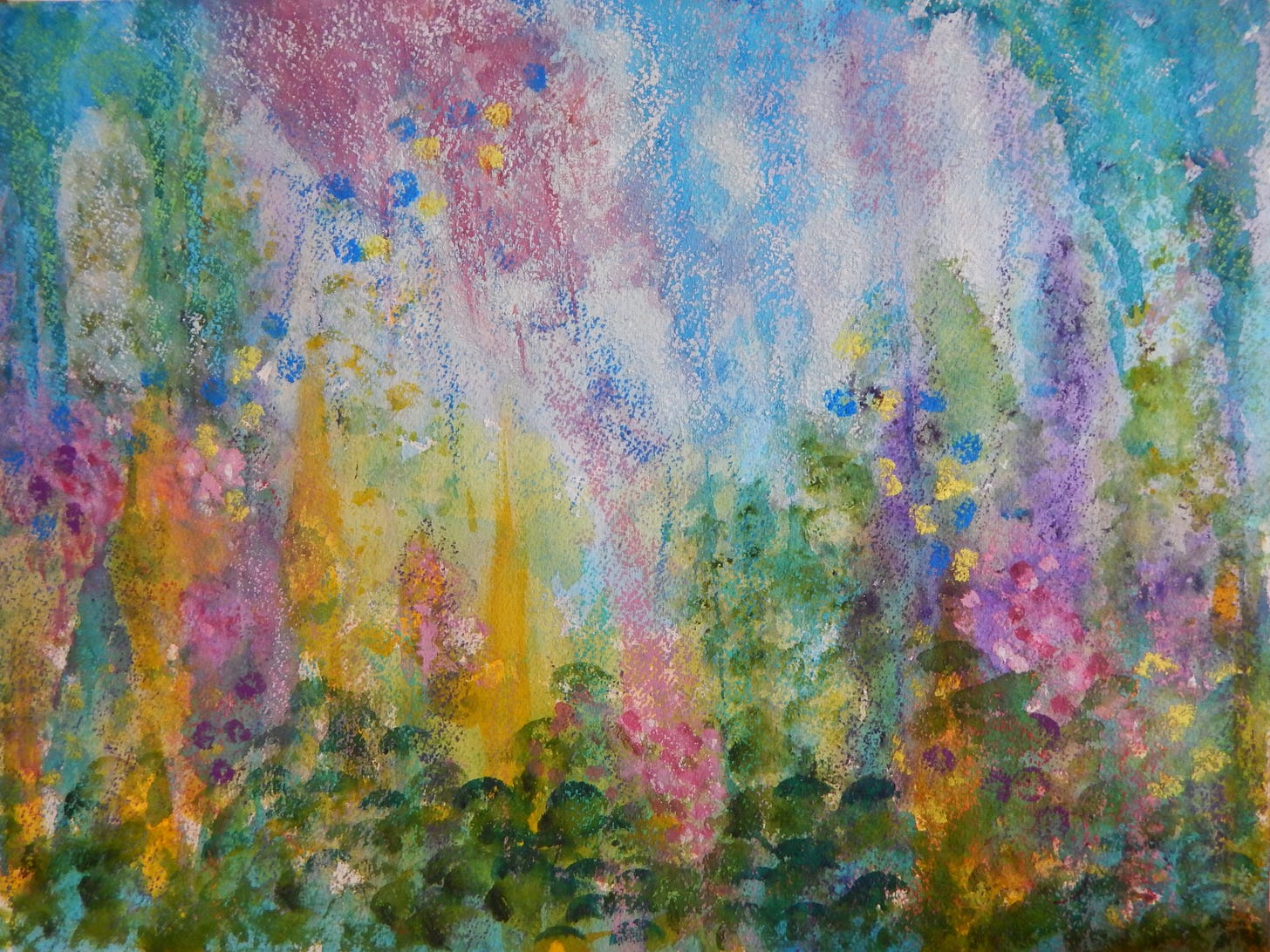

The poem I wrote that day in Moorea captured something of that, as does this painting I created so many years later.

Walking Among Flowers

(Robinson Cove, Moorea)

Walking among flowers

drowning in scent

petals assault me

cool and bent.

Pistils are pounding

stamens stab

colors exploding

stun and grab.

Walking among flowers

I die a keen death

bloodied and trampled

borne by my last breath

I lay like a light

on the garden wall,

then swooping, swallow

flowers and all.

Sometimes beauty can be as “red in tooth and claw” as the untamed wilderness Tennyson wrote about. Its purpose, perhaps, is less to simply sooth or sate or inspire us (although it does all that) than to break us apart and open us up. Much like all great art must do.

Think of Van Gogh’s starry nights, or Picasso’s abstracts, or O’Keefe’s flowers. Was Monet’s impressionism or Seurat’s pointillism pretty ways to put paint on canvas, or ways to reveal how light and color and shapes and all manner of things break apart and open up and take us in, immersing us in the stream of things?

“Walking Among Flowers” is my way to revisit again and again that shattering into the stream of things. Other poems emerged from that journey. They feed me still so many years later, allowing me to enter once more into those deeply felt experiences that have shaped me ever since, and continue to do so. “Isle of Pines” is another such poem. I’ll take you there soon.