May can be tough on mothers. Especially for those waiting for a call on Mother’s Day that never comes. I’ve had my share of those. This year was another. Which is why I revisited a tribute I wrote about my son ten years ago during an especially hopeful time in his life, right after the birth of his daughter. I thought he’d finally beaten down his addiction, and the life I always hoped for him was taking off. Reading this still gives me hope. He did it once. He can do it again. And whether he calls me or not on Mother’s Day, there’s a love bond between us that cannot be broken.

Tribute to My Wild Child, My Son

It always amazed me as my children were growing up how they had come to be, in some uncanny way, the embodiment of very different parts of my psyche. My daughter was growing up to be the woman I had always wanted to be—beautiful, brave, strong, independent and self-confident. While my son was turning out to be the kind of boy that I and so many young women were drawn to-—handsome and charming, sweet and funny, wild and reckless—a born rebel who cherished his freedom, testing limits and bending rules. Living with him was like living on a roller-coaster ride, full of thrills and chills that never seemed to let up.

Almost from the day he was born he was a handful.

I would ruefully tell other mothers how he entered the terrible twos when he was one and never grew out of it. At the tender age of two he ran away from home–-twice. Once to visit his grandma five blocks away. Another to buy candy. A policeman brought him home that day when he was trying to cross a busy street with a nickel in his pocket. I installed locks on all the doors and gates after that.

Yet he was a loving child, a sweet child, popular with other kids and his teachers, even while he spent much of his early grade school days in the principal’s office. Not because he was a bully, but because he refused to be bullied, or see those he cared about bullied.

When he was 11, we moved on our boat La Gitana in Ventura Harbor. He immediately took up surfing, and learned to row a boat and sail a dinghy. He became an avid sport fisherman, making all his own lures and rigging his own poles.

When we finally did take off on our journey there was always a line in the water and he supplied most of the fish we dined on. He could free dive to depths of 20 or more feet to spear a grouper or capture a lobster.

He made friends easily with other sailors and fishermen who were impressed by his skill and knowledge. He became a certified scuba diver at the age of twelve. He was a true Pisces—at home in the ocean he loved.

Trying to home school him was a challenge, but once I enrolled him in a self-paced program where we mailed his work back to a teacher for grading and feedback, it went better. Not that we didn’t have our moments.

By the time we reached Australia, he was almost 17 and didn’t want to leave. In Australia at the time, many children that age left formal schooling to learn a trade. Often they lived on their own, helped out by the government, or boarded with those who were teaching them a trade. He became friends with a boat-builder who invited him to join his crew. When it was time for us to leave Australia, he begged me to let him stay. It was his dream to become the captain of a sports fishing boat, and this seemed like a perfect opportunity for him to pursue that goal. I interceded on his behalf with his father, who, against his better judgment, allowed him to stay.

I’ll never forget the day we sailed away, leaving our son behind in Australia. I felt like the worst of all mothers, like I was abandoning him. And something in his eyes that day made me wonder if he was thinking the same thing.

At the same time, I felt like I was giving him an opportunity to live the kind of life he wanted to live. He was always a free spirit, fiercely independent, an adventurer, a wanderer, even at the tender age of two. I trusted he had what it takes to make it on his own. To this day, I don’t know if I made the right decision.

We exchanged letters and talked to each other as much as we were able as we sailed up the Red Sea and through the Mediterranean, then the Panama Canal on our way home. Always I asked if he was ready to come back on the boat, or fly home to stay with his grandparents. Always he said no, he was fine. But I never really knew. I learned later that the old guy he had gone to work for was hospitalized and eventually died. I heard tales about him drifting around working as a carny, and later for a Mafia-type family who owned a string of Italian restaurants.

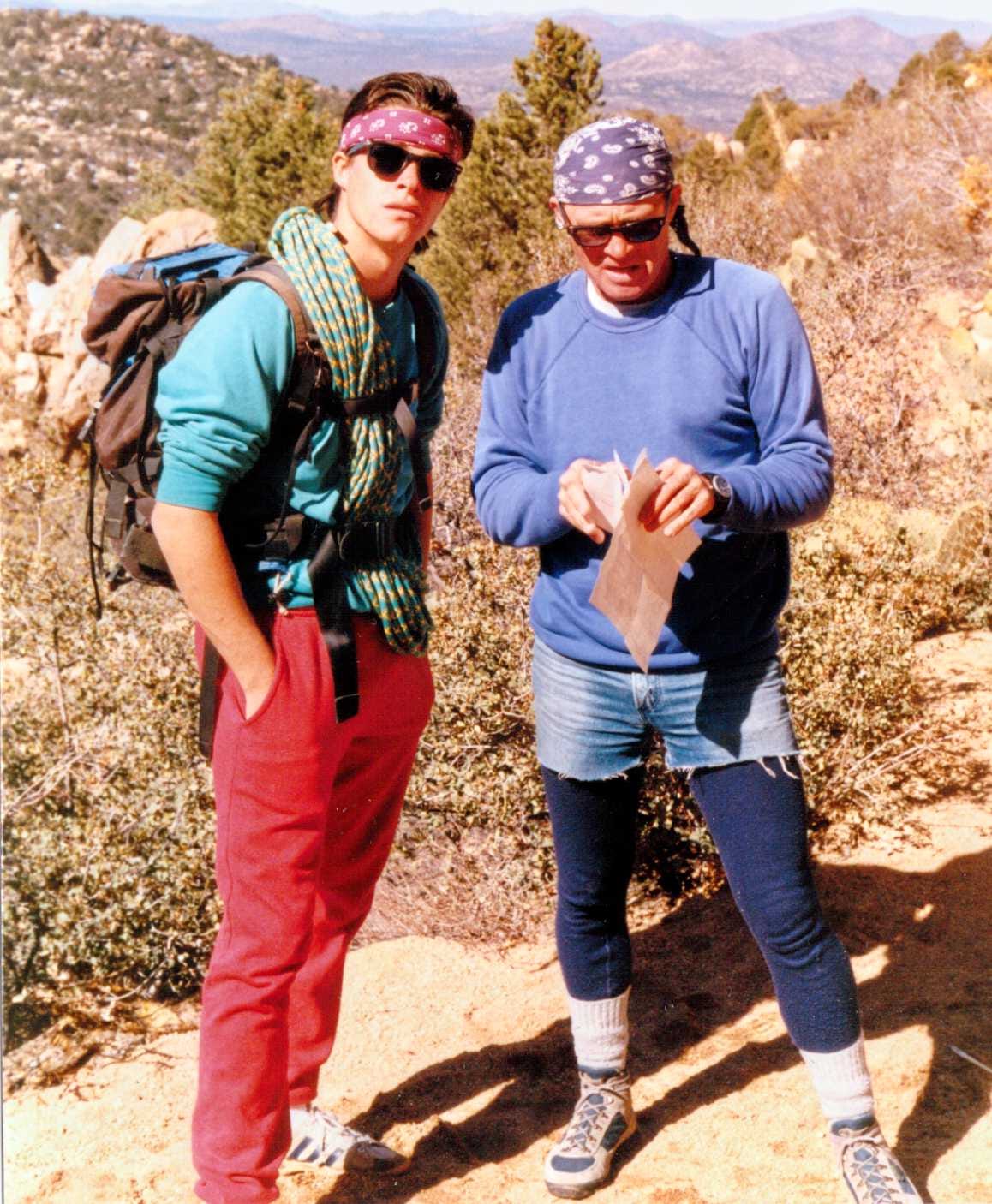

He was 18 when he flew home around the same time we returned from our travels, and he was tall and handsome and had an Aussie accent. He seemed happy and confident. He spent some time with his grandfather, going mountain climbing and obtaining his GED.

Eventually he became a commercial diver, working on the oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico, helping raise a sunk ship off the coast of Nova Scotia. Then he moved to New Orleans.

Two years later when he returned home to California he was a heroin addict.

That’s when the roller-coaster ride became a nightmare. He couldn’t hold a job, couldn’t stay clean. He spent years on the street, in and out of rehab, in and out of jail and prison, in and out of hospitals when he overdosed. We took him in when we could, until we couldn’t anymore. On more than one occasion I moved out with him, thinking hands-on mom-care would help. It didn’t. He tried NA, tried methadone, tried Suboxone. They worked until they didn’t.

The worst part was when I didn’t know where he was. I didn’t know if he was sleeping on a park bench or rolled up on someone’s couch, or lying in a ditch. When he was in jail, or even in the hospital, there was always hope. He was safe, for now. And maybe at last he’d hit bottom. Maybe this time he would begin to turn his life around.

Yet even in the midst of all this he showed strength and resilience, street-wise resourcefulness, and a basic goodness that would inspire him to share the little he had with those who had less.

He saw himself as a “Rider on the Storm,” riding a long wild wave that would surely crash him on the rocks unless he could hold on tight and ride it out, and manage to turn it at just the right moment. He couldn’t control it, and he couldn’t stop it, but he could, perhaps, outlast it. And he did.

He claims now I helped save his life. And sometimes I believe him. My love for him was so strong, my prayers so constant, my will so fierce, nothing could make me let go, nothing could tear him away from me. That’s how I saw it, willed it, demanded that it should be. But I know better. A mother’s love isn’t enough to keep a child safe. Yet still, still, we would so believe.

Sometimes I think he’s the bravest person I’ve ever known. No one else that I know could survive what he’s survived. I know I wouldn’t. Even his father, strong as he is, would not have survived that craziness. Few do, I’m told. Only fifty percent of heroin addicts survive their habit, and only half of those who do eventually lead drug-free lives.

I’m proud of him for being a fighter, a survivor, for not giving up, for having the stamina and courage to start over again and again and again—with nothing, no job, no money, no prospects.

I’m proud of him for winning the heart of the woman he now loves, for helping to bring their child into the world and raising her together, for caring for this child with such love and tenderness. For becoming the Father, the rule-maker rather than the rule-breaker, the Authority Figure in his young one’s life, someone she will look up to, and trust to care for her and keep her safe.

I think of those fairy tales and journeys heroes take, how they go into the dark, scary places of the world, do impossible deeds, overcome unimaginable challenges, fight off terrifying monsters, then save the princess and ride away with her on a white horse. To some degree, in some measure, he’s done all that.

I see him as the warrior turned woodsman who has built a home on the edge of the forest. All the scary things are still out there, but now he’s a seasoned fighter, and he has something other than himself to protect and keep safe. He’s guarding hearth and home, this dragon-slayer, demon-hunter, who has lived with and among dragons and demons for so long.

His body art tells the story of his survival and his path to recovery. Draped along his upper chest are the words “Riders on the Storm” to remind him where he’s been, he tells me. On his shoulders and across his back are nautical stars and a compass rose to guide him through the storm.

On his arm is an anchor with the word “Family” wrapped around it, to help keep him grounded and remind him of what’s he’s fighting for. Beneath his heart are the infant footprints of a son he almost lost and is seeking to regain. Soon to come, he tells me, are the fingerprints of his tiny daughter whose hold on his heart is so fierce.

Perhaps we all live at the edge of a dark forest, at the edge of the wild, with the dark scary things we fear forever yawning at our backs—addiction, disease, poverty, financial ruin, failure, loss of loved ones, war, famine, even enslavement for some. Perhaps our life journey is to keep ourselves strong enough to survive the darkness, and bright enough to face the light and keep walking toward it.

I trust we all shall continue doing so.

NOTE – His journey is still ongoing. I wrote that tribute ten years ago. He had five years sober. Now he’s out riding that storm again. Re-reading this post somehow comforts me. He’s strong, he’s resilient, he’s good and decent. He will survive.

It made me fill with tears reading this Deborah. We have to keep faith in our kids above all else. If a mother can’t then who can?

Love and strength to you xx

Thank you for sharing such a personal journey. Life is a fertilizer for that food of love we call poetry.